JOHANNES THOPAS (Arnhem c.1626 – c.1690/95 Assendelft?)

Johannes Thopas (Arnhem c.1626 – c.1690/95 Assendelft?)

Portrait of Dirck Jacobsz Bas (1569–1637)

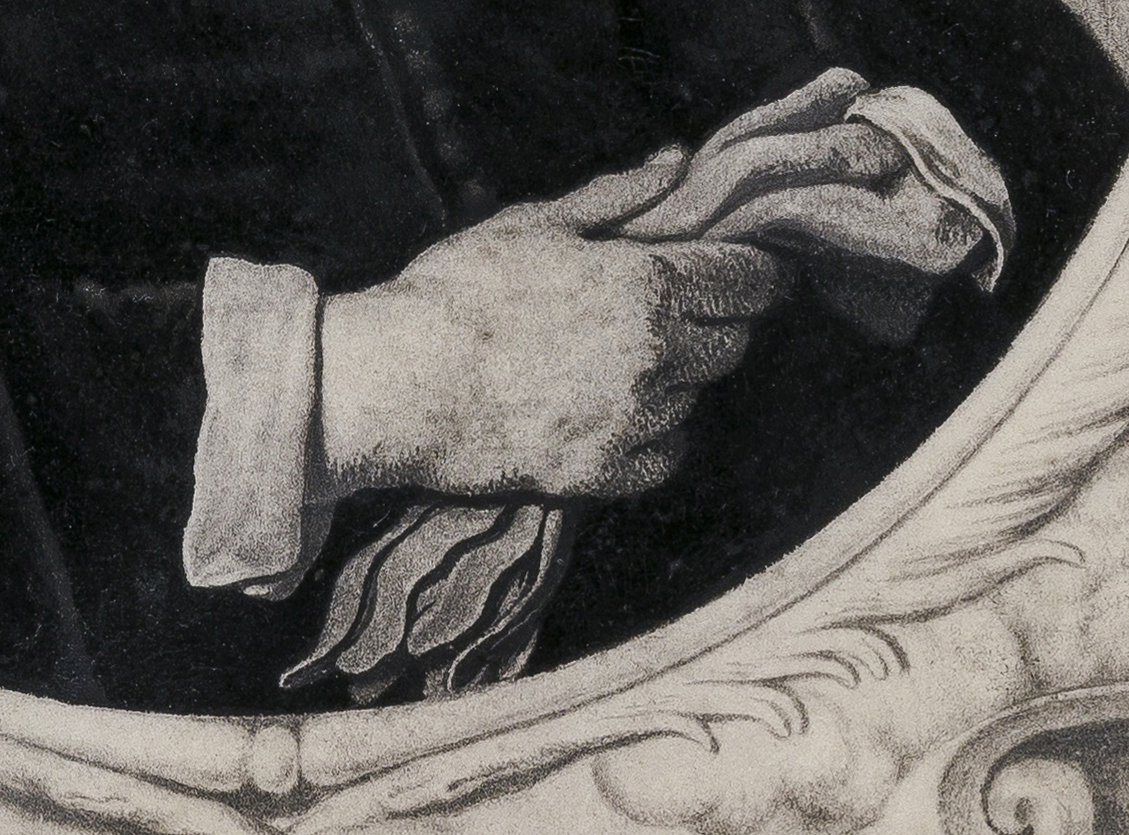

Black lead, black chalk, black wash, grey ink framing lines, on vellum, image size 277 x 196 mm (10.9 x 7.7 inch), sheet size 309 x 241 mm (12.2 x 9.5 inch)

Inscribed in brown ink ‘Theodorus Bas Jacobi / F’ (in central cartouche)1

Provenance

~ Commissioned by Theodorus Kerckrinck (1638–1693), Amsterdam and Hamburg, after 1661

~ With Lodewijk Houthakker, Amsterdam

~ Sotheby’s, Amsterdam, 11 November 1997, lot 106, repr.

~ With Jan Six Fine Art, Amsterdam, 2013

~ Christie’s, London, 5 July 2017, lot 54, repr.

~ Private collection, The Netherlands

Literature

~ S.A.C. Dudok van Heel a.o. (reds.), Van Amsterdamse burgers tot Europese aristocraten: hun geschiedenis en portretten, The Hague 2008, vol. II, p. 579, fig. 391

~ B. Koene, ‘Portrettist Johan Thopas en de zijnen’, De Nederlandsche Leeuw 127 (2010), pp. 62-73, fig. 4

~ I. Nijenhuis, ‘”Uytten buyck van ’t landt”. Holland en de Staten-Generaal (626-1630)’, in: iI. Nijenhuis a.o. (eds.), De leeuw met de zeven pijlen. Het gewest in het landeljk bestuur, The Hague 2010, pp. 49-71, repr. on p. 55

~ H. Proud, ‘Exciting Revelations in the Michaelis Collection’, FMC News, Spring Summer Edition 2011 (digital publication)

~ E. Kok, Culturele ondernemers in de Gouden Eeuw. De artistieke en sociaal-economische strategieën van Jacob Backer, Govert Flinck, Ferdinand Bol en Joachim von Sandrart, dissertation Universiteit van Amsterdam 2013, pp. 193-94, note 548

~ R.E.O. Ekkart (ed.), Deaf, dumb & brilliant: Johannes Thopas, master draughtsman, exh. cat. Amsterdam (Rembrandthuis) and Aachen (Suermondt-Ludwig Museum) 2014, pp. 70, 121, cat. no. 31, repr.

~ M. Hell, E. Los, N. Middelkoop and T. van der Molen (eds.), Hollanders van de Gouden Eeuw, exh. cat. Amsterdam (Hermitage Museum) 2014, p. 75, fig. 62

Exhibited

R.E.O. Ekkart (ed.), Deaf, dumb & brilliant: Johannes Thopas, master draughtsman, exh. cat. Amsterdam (Rembrandthuis) and Aachen (Suermondt-Ludwig Museum) 2014, pp. 70, 121, cat. no. 31, repr.

***

This portrait of Dirck Jacobsz Bas (1569–1637) belongs to a series of similar works by Thopas, which has become known as the ‘Kerckrinck Series’, named after Theodorus Kerckrinck (1638–1693), who commissioned the set.2 Kerckrinck, doctor of medicine and adviser to Cosimo III de’ Medici, probably ordered the drawings shortly after the death of his father Dirck Godertsz Kerckrinck in 1661. Nine drawings from the series are known today, while five others are documented only from descriptions. Originally, the series must have been twice as large.

Other drawings from the series are in the Metropolitan Museum, New York (Godert Kerckrinck), the Albertina in Vienna (Albert Bas, Mathias Bode and Theodor Kerckrinck), the Rijksprentenkabinet in Amsterdam (Petronella van Roy Livini) and the Courtauld Institute, London (Elisabeth Bas).3 The series dates from around 1662, and all are drawn copies after existing portraits, the sitters in many cases long deceased.

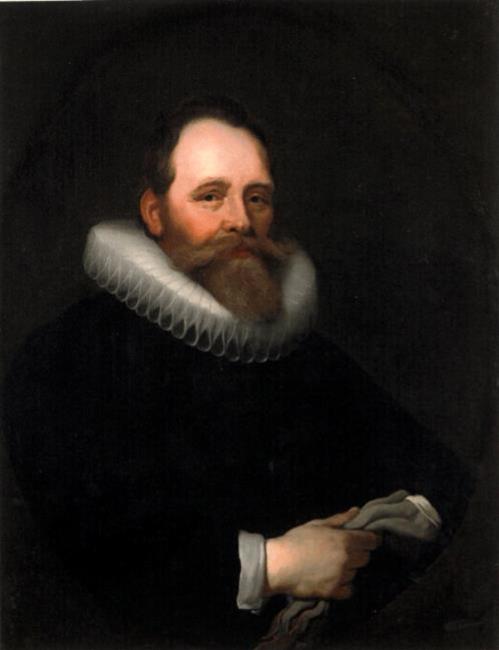

The sitter of the present portrait, Dirck Jacobsz Bas was one of the founders of the VOC (Dutch East India Company), was twelve times Burgomaster of Amsterdam, deputy in the States General, and was knighted by King Gustav Adolf of Sweden in 1616, because of his role in the peace negotiations between Sweden and Russia. The model for the drawing by Thopas is a painting by Jacob Backer in the Michaelis collection in Cape Town (fig.).4 The sitter’s daughter Agatha Bas was famously painted by Rembrandt, now in the Royal Collection in London (fig.).5 Dirck Bas was the father-in-law of Dirck Kerckrinck, who married Margaretha Bas. Our drawing is particularly close to the portrait of Godert Dircksz Kerckrinck in the Metropolitan Museum, New York (fig.).6 The designs for the elaborately drawn cartouche Auricular frames in the drawings in this series, and others by Thopas, have sometimes been credited to the silversmith Jan Lutma, but are likely by Thopas himself.

Until only a few years ago, Thopas remained unknown even to specialists in the field of Dutch art. This was changed by a monographic exhibition in the Rembrandthuis Museum in Amsterdam and the Suermondt-Ludwig Museum in Aachen in 2014, which was accompanied by a scholarly catalogue presenting a wealth of new information about the artist.7 Thopas lived a peripatetic existence from his earliest days: born in Arnhem, he likely spent time in Emmerich as a young child. When he was about fourteen, his family moved to Utrecht, where he remained until 1656. He then relocated to Amsterdam, and, sometime in the 1660s, to Haarlem. Thopas spent his later years in Assendelft, and, probably, Zaandam.

Research established that Thopas was both deaf and mute, conditions that profoundly shaped his life and career. Deemed unable to live independently because of these conditions, the artist remained under the legal guardianship of various family members throughout his life. He neither married, nor, it seems, supported himself financially. Nevertheless, Thopas found regular if not copious opportunities to acquire artistic commissions, including from the leading Amsterdam surgeon Dr Nicolaes Tulp. The almost calligraphic signatures and inscriptions on his drawings are evidence that a deaf-mute Dutchman of the seventeenth century could indeed achieve some measure of literacy, and could learn the art of writing extraordinarily well.

Throughout his artistic career, which stretched from the mid-1640s to the mid-1680s, Thopas specialised in portrait drawings using plumbago (leadpoint) and wash on vellum. Around seventy such works are accounted for today. Almost without exception, they are small, microscopically conceived and finished productions that recall miniature paintings. Especially during his Amsterdam period, Thopas lavished attention on elaborate backgrounds and cartouche borders, of which the present well-preserved drawing is a notable example. ‘Finished’ portrait drawings were still rarely produced during the Dutch seventeenth century, and Thopas must be regarded as something of a pioneer in this genre. From the point of view of the social history of art, Thopas’s sustained activity provides evidence that hearing and vocal impairment did not preclude a career as a portraitist in Golden Age Holland.

1. The ‘F’ is thought to be an abbreviation of ‘filius’ (son); I am grateful to Prof. R. Ekkart for this information, email correspondence, 11 October 2022.

2. R.E.O. Ekkart (ed.), Deaf, dumb & brilliant: Johannes Thopas, master draughtsman, exh. cat. Amsterdam (Rembrandthuis) and Aachen (Suermondt-Ludwig Museum) 2014, pp. 119-122.

3. See Ekkart (ed.), loc. cit.

4. Oil on canvas, 87 x 66.7 cm, inv. no. 14/2; P. van den Brink, ‘Tussen Rubens en Rembrandt. Jacob Adriaensz. Backer als portret- en historieschilder in Amsterdam’, Kroniek van het Rembrandthuis (2016), p. 4-39, esp. p. 22-24, ill. 18.

5. Signed and dated 1641, oil on canvas, 105.4 x 83.9 cm, inv. no. RCIN 405352; J. Bruyn, B. Haak, S.H. Levie, P.J.J. van Thiel and E. van de Wetering (eds.), A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, Dordrecht/Boston/Lancaster 1982-…, vol. III (1989), cat. no. A 145. Rembrandt van Rijn (Leiden 1606-Amsterdam 1669) - Agatha Bas (1611-1658) (rct.uk)

6. Black lead, grey and black wash, on vellum, 315 x 237 mm, inv. no. 2013.560; Ekkart, op. cit., p. 119, cat. no. 27.

7. Ekkart (ed.), op. cit.