GERARD WIGMANA (Workum 1673 – 1741 Amsterdam)

Gerard Wigmana (Workum 1673 – 1741 Amsterdam)

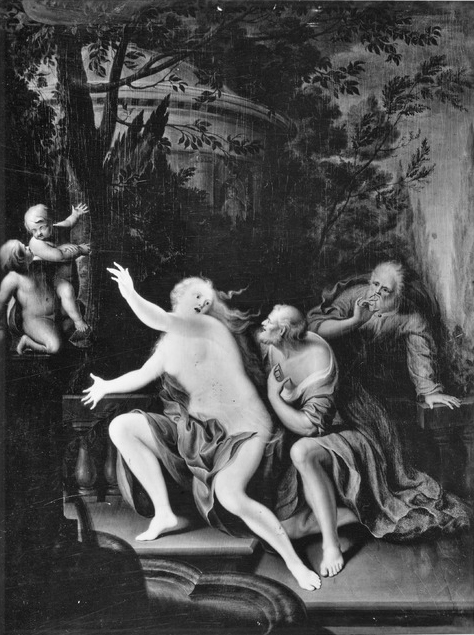

Bathsheba at her Bath

Oil on panel, 54.3 x 40.2 cm (21.4 x 15.8 inch); presented in a modern giltwood frame of 18th-century model

Signed ‘Wigmana’ (lower right)

Provenance

~ Jonas Jonasz Witsen (Amsterdam 1733 – 1788 Amsterdam); his sale, Amsterdam, 16 August 1790, lot 86: ‘J. Wigmana. Deeze bevallige Ordonnantie verbeeld in een aangenaam Thuingezigt, by een Fontyn die op de voorgrond geplaatst is Batzeba, gedeeltelyk op een cierlyk Rustbedde leggen, welke door een Vrouw gewassen word, neevens dezelfde staat een andere een Spiegel vast houdende, en een ander over een Baluster ziende, verder ziet men de Koning David boven op het Palys; dit stuk is fraay en uitvoerig gepenceelt. 21 ½ = 16 dm. Paneel’, sold for 31 florins to ‘Yver’

~ Private collection, France

***

This recently discovered signed panel by Gerard Wigmana is an important addition to the small painted oeuvre of this interesting artist, arguably the leading painter of Frisian descent of the first half of the eighteenth century. It is one of the most notable of his celebrated and highly refined paintings with mythological, religious and allegorical subjects still remaining in private hands.

Gerard Wigmana was born in Workum in Friesland as the son of the merchant Jan Tiaerdts and his wife Gaitske Gatzes Wigmana - interestingly, he took the last name of his mother’s family.1 Wigmana developed a passion for painting at an early age, as attested by an episode following the death of his father around 1688: when his mother wanted him to learn a decent trade, Wigmana replied by saying ‘If I can’t learn painting, let me learn weaving,’ meaning he wanted to become a painter at all costs. Wigmana took drawing lessons with a local glass painter and studied with the German painter Joachim Burmeister, before becoming a student of Jelle Sybrandi, a member of the Dutch painters’ society. He then undertook a Grand Tour to the South from 1698 to 1702, visiting Paris, where he studied at the Académie Royale for a year and a half at the outset of the journey, after which he continued to Rome, where he arrived on 14 November 1699 and entered the studio of the painter Giovanni Maria Morandi, himself a pupil of Pietro da Cortona. He also met the artist Daniel Seiter in the Eternal City, and supplied details of the latter’s life to the biographer Arnold van Houbraken. In Rome he copied three paintings by Raphael, and he is also known to have copied a painting by Titian in Modena.

By 1702 Wigmana had returned North and lived in Dokkum and Leeuwarden, where he married in 1707; he settled as an independent master and the esteem for his talent is indicated by his position as art teacher to Princess Henriette Amalia’s children Johan Willem Friso and his seven sisters, which he held for seven years. The artist then moved to Amsterdam. He furthermore undertook a brief journey to London in 1737. Wigmana’s sojourn in France and Italy, where he studied the works of the great masters of the Renaissance, proved highly influential to his work. According to biographer Johan van Gool, the artist made so many copies of Raphael that he came to be known as the ‘Frisian Raphael’.2 Wigmana held heartfelt opinions about the developments in contemporary painting, which he expressed on paper and were published as Korte schets of denkbeeld, Om tot een groote volmaaktheid in de schilderkonst te geraken, printed posthumously in 1742 by bookseller Jacobus Ryckhoff – Wigmana lists nearly fifty artists he found inspirational. In addition to Raphael, Correggio, Guido Reni, Veronese and Titian are also mentioned.

The paintings that Wigmana produced after his return from the South can be characterised a typical works of the Classicist ‘fijnschilder’ or fine-painter school, who excelled in the refined and minutely detailed depiction of fabrics and textures. He was quite celebrated during the eighteenth century, but was mostly forgotten during the next, and it was not until a publication by Theodor von Frimmmel in 1907 that his name entered the annals of art history.3 Due to this relative obscurity, many of his paintings were attributed to other artists of the period, notably Willem van Mieris and Adriaen van der Werff, and the process of identification of works by Wigmana continues to this day. To date, several dozens of paintings by him are known, mostly depicting mythological, religious and allegorical scenes, but also a number of portraits.

The present recently discovered work, which is in beautiful state of preservation, is a typical example of his elegant style, and is also signed by the artist. The attractive subject of the beautiful Bathsheba is taken from the Old Testament (2 Samuel 11): one night in Jerusalem, King David was taking the air on his rooftop, when he spotted a beautiful woman bathing nearby. When he made enquiries as to her identity, he found out that she was Bathsheba, wife of Uriah the Hittite, one of David’s warriors. The King summoned Bathsheba to his palace, they slept together and Bathsheba became pregnant, which led to several dramatic events. The subject was favoured by painters of the period as it was among very few biblical stories which provided opportunities for depicting the female nude in all its graciousness.

Our work is the only known instance of Wigmana treating this subject. It can however be compared to his Susanna and the Elders in the Bildergalerie in Schloss Sanssouci, Potsdam, dated 1731.4 The themes are closely connected, as in both stories a bathing woman is the main subject – Bathsheba, however, is watched by King David, identified in the present painting by his crown, while Susanna was observed by two elders. Other comparable works by Wigmana are dated around 1715, but as his elegant style seems to have remained fairly consistent, it is difficult to say if the present work was painted in Friesland or Amsterdam.

A sense of explicit eroticism is apparent: Bathsheba’s body is presented to the viewer, largely nude and brightly lit, attended by her maids, her reflection presented in an oval mirror. Sensual content was already present in Dutch genre painting of the seventeenth century, primarily in the form of brothel scenes. Yet, pictures such as the present one suggest a change of style from the Golden Age. They are forerunners of a naturalised and classicised eroticism that would become distinctive of Rococo painting. From this perspective, Wigmana’s Bathsheba could be closely compared to the nudes of the fine-painter artists of his generation, such as Adriaen van der Werff, who painted a series of sensual, mythologically inspired pictures for the open market. These works anticipate the profusion of provocative nudes that, in Europe, would later reach its peak in France in the allegorical, mythological and historical paintings of artists such as Lemoyne, Van Loo, and, primarily, François Boucher.

Two allegorical large-scale works by Wigmana are preserved in the town hall of Leeuwarden, part of an earlier decorative scheme. They are an Allegory of Silence and an Allegory of Legislation, executed by Wigmana circa 1715, shortly before he moved to Amsterdam.5 One of Wigmana’s earliest known works is also still in Friesland, a group portrait of the family of Julius Schelto van Aitzema and Sara van den Broek, with guests and servants, dated 1697, which is preserved in the town hall of Dokkum.6

During the eighteenth century, the present painting formed part of the celebrated collection of Jonas Jonasz Witsen IV (Amsterdam 1733 – 1788 Amsterdam), a member of a dynasty of collectors: his father, grandfather and great-grandfather were also famous collectors – it cannot be excluded that our painting was collected by his ancestors and was inherited by Jonas IV.7

The fact that this major work from Wigmana’s oeuvre has disappeared from sight since it was last mentioned at auction in 1790, illustrates the lack of interest in the artists from his generation during most of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, a fate also shared by major other ‘fijnschilders’ like Dou and Van Mieris. In the last decades, major exhibitions have reinstated the importance of these neglected artists, and their works are now among the most coveted pieces for museum and private collections alike. This reappreciation has also drawn scholars to lesser known – though by no means less interesting – provincial masters such as Wigmana, with the present picture amongst his best surviving works.

1. For the artist, see: B. van Haersma Buma, ‘Gerardus Wigmana. De Friese Raphaël’, De Vrije Fries 49 (1969), pp. 43-65, J. van der Meer Mohr, ‘An attribution to Gerard Wigmana’, Mercury no. 4 (1986), pp. 48-52 and B. van Haersma Buma, ‘Weerzien met Wigmana’, in: It doe yn 't hjoed wer woun. Liber amicorum Sytse ten Hoeve, Sneek 2001, pp. 43-47.

2. Johan van Gool, De Nieuwe Schouburg der Nederlantsche kunstschilders en schilderessen, The Hague 1750, p. 386.

3. Th. von Frimmel, ‘Ein signiertes Werk von Gerard Wigmana’, Blätter für Gemäldekunde 3/7 (1907), pp. 109-113.

4. Oil on canvas, 74 x 56 cm, inv. no. 5551; Eckardt Götz, Die Gemälde in der Bildergalerie von Sanssouci, Potsdam 1980, cat. no. 5551.

5. Oil on canvas, 136 x 125 cm, inv. no. T.H.A. C43b and oil on canvas, 180 x 107 cm, inv. no. XI C 1; see A.Wassenbergh, ‘De decoratieschilders der achttiende eeuw en het stadhuis te Leeuwarden’, Gedenkboek Leeuwarden 1435-1935, Leeuwarden 1935, p.165.

6. Oil on canvas, 125 x 175 cm; Jet Pijzel-Dommisse (ed.), Nederland dineert: vier eeuwen tafelcultuur, Zwolle/The Hague 2015, p. 39, repr. pp. 40-41.

7. For Witsen, see: A.J. Elen, ‘”Ongemeen uitvoerig op Perkament met sapverven behandeld”. De gekleurde tekeningen van Willem van Mieris uit de collectie Jonas Witsen’, Delineavit et Sculpsit, no. 15, May 1995, p. 1-22.