FRANCESCO ALLEGRINI (Cantiano? 1615/20 – after 1679 Gubbio?)

Francesco Allegrini (Cantiano? 1615/20 – after 1679 Gubbio?)

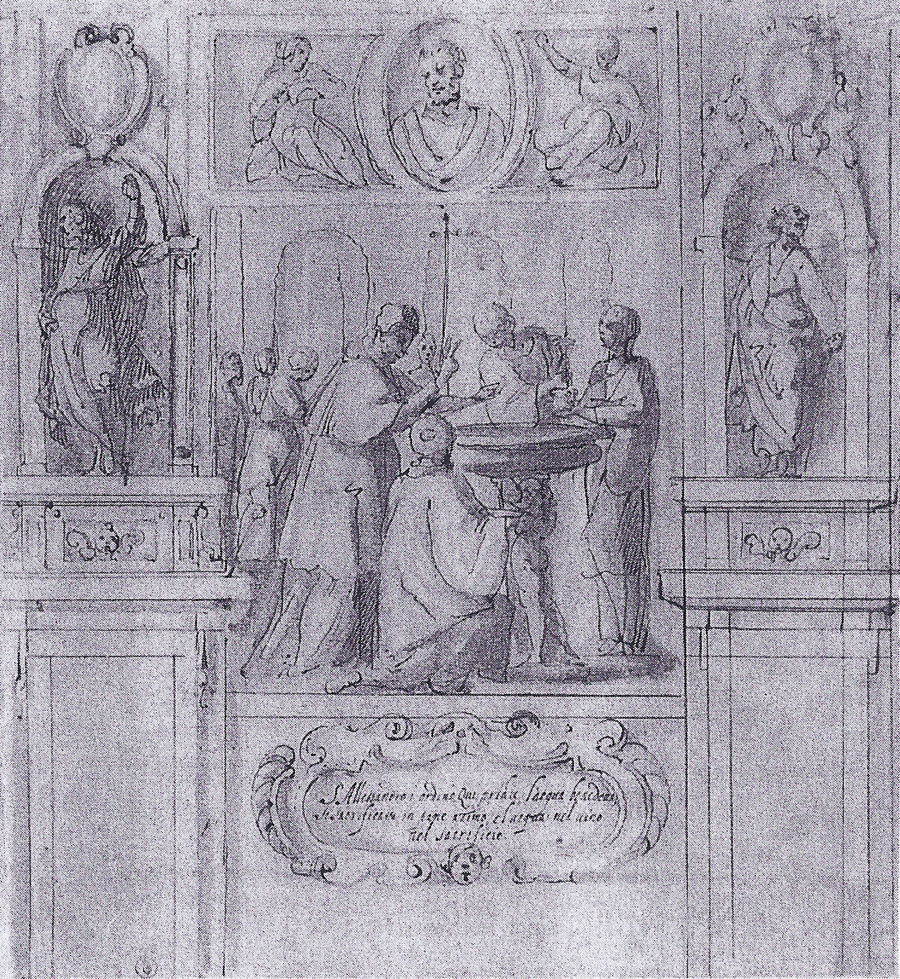

Design for a Wall Decoration with Scenes from the Life of St Anacletus and St Sixtus

Pen and brown ink and red wash, over a sketch in graphite, on two joined sheets of paper, 276 x 321 mm (10.9 x 12.6 inch)

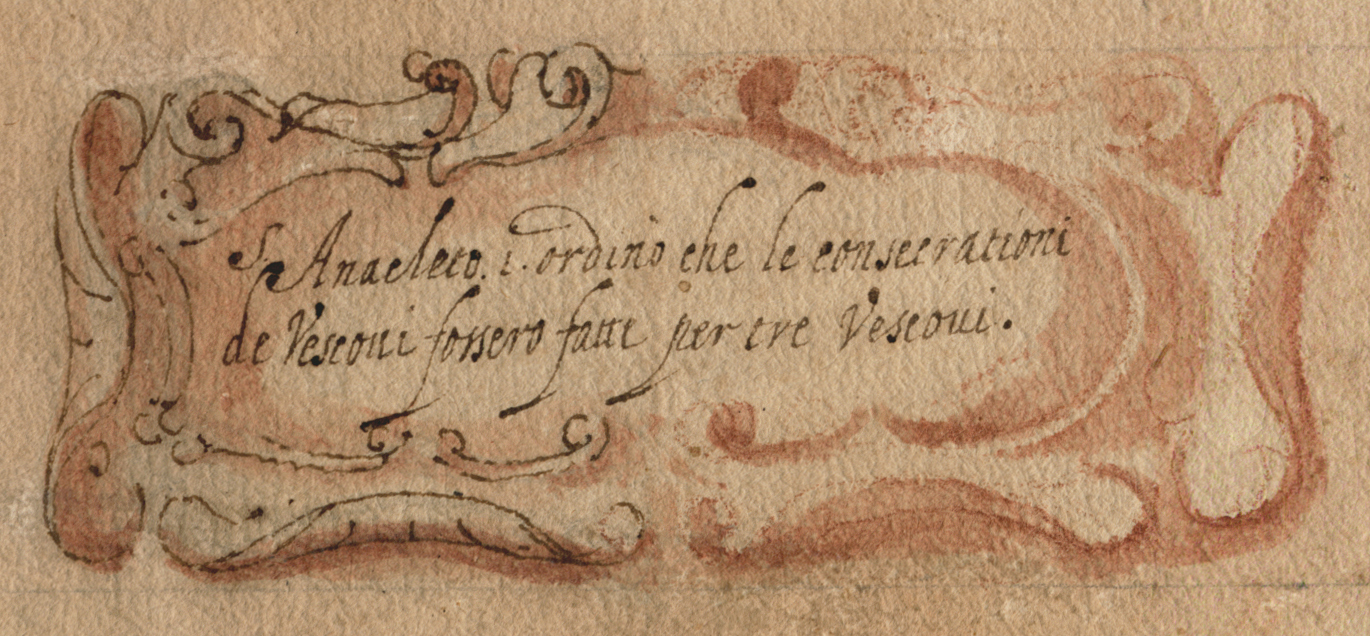

Inscribed (by the artist?) in the courtouches in pen and brown ink with the subjects of the two scenes: S. Anacleto i. ordinó che la consacrationi / de Vescovi fossero fatte per tre Vescovi. (St Anacletus ordained that the creation of bishops can only be done by three Bishops’ And S. Sisto i ordinó che da niuno fussero toccate / le cose sacre et in particolar da donne: l ‘istesso / confirmó Sant’ Urbano Papa (St Sixtus ordained that the holy things can be touched by no-one, and especially not by women: the same has been confirmed by St Urbano Pope)

Bears old attribution in pen and brown ink Gius.pe d’Arpino (lower left)

Provenance

~ Anonymous sale, London, Sotheby’s, 30 April 1990, lot 24

~ Purchased at the above sale by Ralph Holland (1917-2012), until 2013

Literature

S. Prosperi Valenti Rodinò, ‘Francesco o Flaminio’, in: Gianni Carlo Sciolla (ed.), Nuove ricerche in margine alla mostra: Da Leonardo a Rembrandt, Disegni della Biblioteca Reale di Tornino. Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Studi, Turin 1990, pp. 230-31, reproduced fig. 5

***

Francesco Allegrini was one of the artists working in the wider orbit of Pietro da Cortona.1 Active chiefly in Rome, Gubbio and Liguria, he is known above all as a painter of decorative Cortonesque frescoes, of altar paintings, and of easel paintings with battle scenes. His masterpiece is the ceiling with the story of Dido in the Palazzo Pamphilj, Rome, executed in the early 1650s for Pope Innocent X Pamphilj. Francesco was the son of the painter Flaminio Allegrini (1587-c.1663), one of the closest followers of the Cavalier d’Arpino, whose influence can be felt also throughout the oeuvre of Franceso, and which also explains the early attribution to the Cavalier on our drawing. There has been much confusion in the literature between father and son Allegrini, starting with a mix-up between them in Orlandi’s Abecedario pittorico (Bologna 1704) and in Nicola Pio’s Vita (manuscript by 1724). If Pio’s indication that Francesco lived tot the age of seventy-six is correct, he died around 1690.2

The name of Allegrini is especially familiar to drawing specialists. A great number of his small and lively pen and ink drawings with figure scenes survive. Some of them are studies for extant frescoes. Four volumes with a total of 589 drawings are preserved in Leipzig in the Museum der bildenden Künste. The National Gallery of Scotland owns some seventy drawings by Francesco, mainly individual figure studies. An equal number of his figure compositions is in the Metropolitan Museum, New York, and numerous other drawings are scattered in museums and private collections.

The best characterisation of Francesco’s drawings is still that given in 1924 by Hermann Voss, who was the first to discuss the artist as a draughtsman. He stressed his natural gift for drawing and his taste for the minute; he saw the essence of his graphic art in the graceful, appealing penmanship. Voss examined other techniques used by Francesco: chalk, wash, and mixed media applied in a looser manner.3

Our drawing has a scene from the life of St Analectus at the left; Analectus, also known as Cletus, died c. 92, was head of the Church from c.79 to his death c.92. He was the third pope, following St Peter, and Pope Linus. Tradition has it that Anacletus divided Rome into twenty-five parishes. At the right is a scene from the life of St Sixtus, head of the Church as Sixtus I between c. 115 to his death c. 124, during the reign of Emperor Hadrian. Sixtus is credited as having instituted several liturgical and administrative traditions. One of his ordinances, according to the Liber Pontificalis, is that none but sacred ministers are allowed to touch sacred vessels, which is represented here.

A design for another section for the same project is preserved in the Biblioteca Reale, Turin (fig.).4 Executed in the same media, the Turin sheet represents a scene from the life of another Pope from the early Christian period, Alexander I, reigned c. 107 to c. 115. A similar design for a decorative fresco with a scene from the life of St Sebastian is preserved in the National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh (fig.).5

SOLD

1. For the artist as a draughtsman, see for instance J. Bean, 17th Century Italian Drawings in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1979, pp. 16-33; J. Gere and P. Pouncey, Italian Drawings in the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum, Artists working in Rome c. 1550 to c. 1640, London 1983, pp. 26-28; Marcel Roethlisberger, ‘Landscapes by Francesco Allegrini’, Master Drawings, XXV, 1987, pp. 263-69.

2. N. Pio, Le vite di pittori scultori et architetti, ed. C. and R. Enggass, Vatican City, 1977, p. 35.

3. H. Voss, ‘Über Francesco Allegrini als Zeichner’, Berliner Museen, 45, Berichte aus den preussischen Kunstsammlungen, 1924, pp. 15-19.

4. Pen and brown ink and reddish wash, 261 x 245 mm; A. Bertini, I Disegni Italiani della Biblioteca Reale di Torino, Rome 1958, p. 67, no. 533, repr.

5. Pen and brown ink and brown wash, 242 x 259 mm; K. Andrews, National Gallery of Scotland: Catalogue of Italian Drawings, Cambridge 1968, no. D915, fig. 12.