ANDREA SACCHI (Rome 1599 – 1661 Rome)

Andrea Sacchi (Rome 1599 – 1661 Rome)

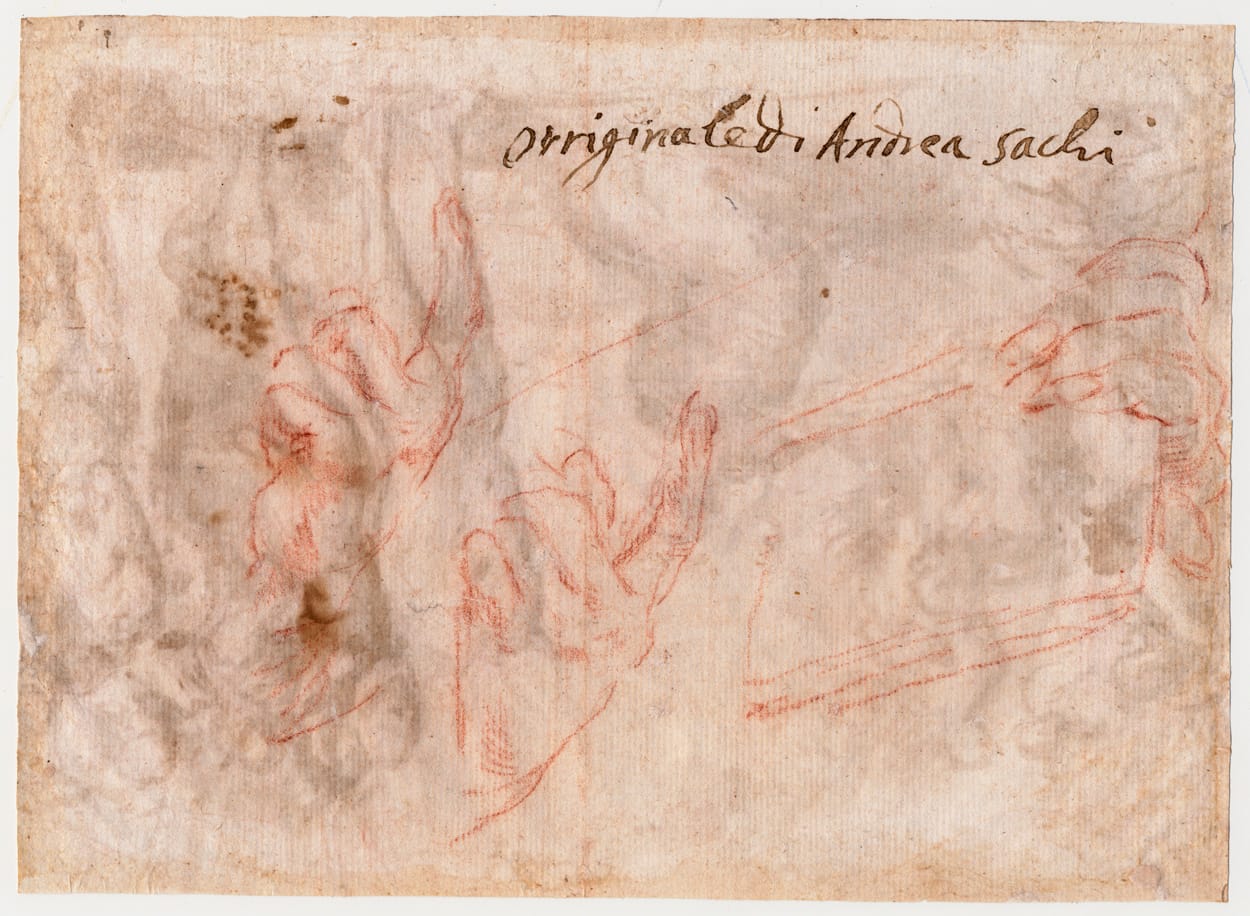

Abigail Bringing Gifts to David (recto); Studies of Hands (verso)

Brush with light red and brown-grey wash over red chalk, watermark heart-shaped (?) device, 181 x 250 mm (7.1 x 9.8 inch)

Inscribed ‘orriginale di Andrea Sachi’ (brown ink, verso)

Provenance

~ Private collection, France, 1950s/1960s

~ Private collection, USA

***

This hitertho unknown drawing is an important addition to the drawn oeuvre of the Roman Baroque artist Andrea Sacchi. “[He] worked with an uneasy mind; knowing perfectly well the difference between the good and the better, he was never content.” So reported Sacchi’s biographer. The artist himself said that other famous artists “frighten me and make me lose heart.” The most vocal leader of Baroque classicism in the 1630s, Sacchi argued against the exuberant Baroque manner of Pietro da Cortona and Gianlorenzo Bernini. He debated with Cortona in the Academy of Saint Luke, maintaining that history paintings should have few figures, because simplicity and unity were essential to classicism. Cortona, in contrast, believed in compositions with a main theme and many episodes, implying greater complexity and numerous figures. Sacchi’s painting style paralleled that of his friend, the sculptor Alessandro Algardi. Like another friend, Nicolas Poussin, Sacchi increasingly refrained from sensory appeal. He repeatedly demonstrated his psychological penetration and concentration on essentials. By the end of the 17th century, the cool, serene approach of his classicism triumphed, much promoted by his pupil Carlo Maratti.

The Biblical subject of Abigail and King David is fairly rare in the visual arts. As related in 1 Samuel 25, David was on the run from King Saul, who rightly considered David a threat to his throne. Abigail was married to the rich Nabal, who was asked for supplies by David. Her husband having refused the supplies, Abigail feared for the safety of her people, gathered provisions and presented herself to David, who was about to ride out to convince Nabal in less friendly terms. Abigail has since been considered a model of diplomacy and wisdom.

The subject intrigued Sacchi, and in addition to our drawing he made at least two other drawings of the theme. The first, highly comparable to our drawing in terms of composition and handling, and of identical dimensions, is preserved in the British Museum, London (fig.).1 The London sheet has been dated to the late 1630s, and our drawing must be placed in this period too. As Ann Sutherland Harris observed, Sacchi treated the subject again several years later, around 1640, in a drawing in the collection of Dr Joseph Imbriglia, Pittsburgh.2Xerxes in the Desert in the Louvre.3

Although Sacchi treated the subject in the aforementioned three drawings, no painting of Abigail before David is known. As observed by Nicholas Turner, the developing composition shows knowledge of Pietro da Cortona’s lost painting of the subject, painted in the late 1620s and known from an engraving by Benedetto Eredi.4 The influence of Guercino’s famous picture painted in 1636 for Cardinal Antonio Barberini can also be noted (formerly Bridgewater House, now lost).

SOLD

1. Brush with light red and brown-grey wash over red chalk, 182 x 259 mm; British Museum, inv. no. 1975-7-26-1; Nicholas Turner, Italian Drawings in the British Museum, Roman Baroque Drawings, London 1999, vol. I, no. 287. The sheet was acquired in 1975 as the work of Andrea Camassei, but was soon correctly identified as Sacchi by Ann Sutherland Harris.

2. Red chalk and red wash, incised for transfer, 147 x 197 mm; collection Dr Joseph Imbriglia, Pittsburgh, USA; Ann Sutherland Harris, review of Turner ‘Roman Baroque Drawings’, Master Drawings, 39, Winter 2001, p. 424, fig. 1.

3. Brush and brown ink, brown wash, over red chalk, 259 x 232 mm; Musée du Louvre, département des arts graphiques, inv. no. 14146.

4. Turner, loc. cit.